See. Do. Be. Free.

Issue 005

An Open Letter to the Community around this year's theme.

Greetings,

Each year we choose a theme to help guide our work.

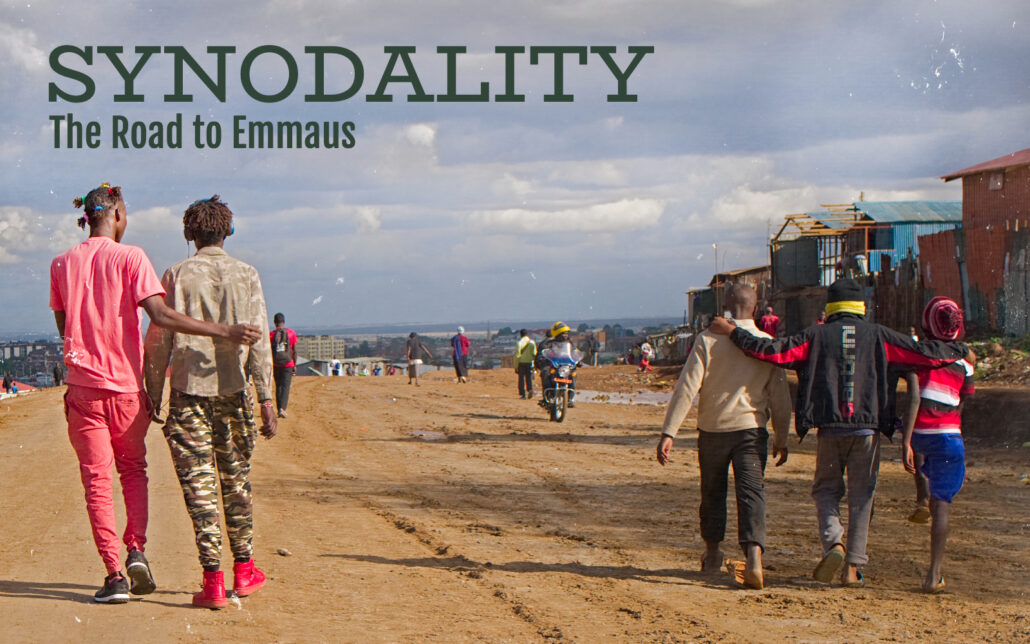

This year’s theme is synodality. It means “walking together.” We are practicing the art of walking together as we learn how to create cities of peace for all people, where everyone belongs, especially the most vulnerable.

One of my favorite passages in Scripture is the Emmaus Road story in Luke 24:13-35. It’s one of the great synodal texts in all of literature.

Cleopas and his companion are fleeing Jerusalem on their way to Emmaus. They are traumatized by the murder of Jesus and perhaps their own complicity in it. It’s Easter day, but they have no idea that Jesus has been resurrected.

While walking to nowhere* Cleopas and his friend begin “talking” and “discussing” what happened in Jerusalem. The word for “talking” here is homilein from which we get the word homily. In other words, they were homilizing as they walked. But unlike most homilies, this was an intensely heated argument. The word “discussing” is derived from the Greek root balletefrom which we get the word “ballistic.” They were literally going “ballistic.” And who could blame them? They had witnessed the brutal lynching and murder of Jesus. They are fleeing for their lives, on their way to nowhere, trying to forget what was behind them.

That’s when a stranger joins Cleopas and his friend. Luke tells us that “their eyes were kept from recognizing him.”

The stranger walks with them and listens intently to their heated discussion. Then he does something very odd. “Beginning with Moses and all the prophets, the stranger interpreted to them the things about himself in all the Scriptures” (Luke 24:27).

What’s odd here is that the stranger takes on the role of a rabbi and narrates the sacred stories as if the stories were about him. This is very strange indeed! Something about his interpretation makes their “hearts burn within.” And so, they invite the stranger to be their guest for supper. The stranger accepts their hospitality and assumes his place at the table. And here, the stranger grows even stranger. Much to their surprise, the guest begins to play the role of the host. He re-enacts the last supper. He gives Cleopas and his companion the bread. That’s when the penny drops. That’s when their eyes are opened and they see the risen Christ. They immediately change course and return to Jerusalem with joy.

What we are witnessing here is a theophany – an appearance of God. God shows up incognito, as God often does.

But here, God takes the form of a victim who has been lynched and murdered and who returns to address the lynch mob who killed him.

And this is where things are truly bizarro.

Not once in all of the resurrection narratives does the crucified risen one return with thunderbolts. The lynched and murdered one does not come back and rub our nose in the murderous mess we made. The resurrection accounts begin with some variation of, “Do not be afraid” and “Peace be with you.” The absence of vengeance is ginormous and demands attention. There’s not even the slightest hint of resentment. None! Zip! Zero! It’s hard to overstate how really, really weird this is.

This is why theologian, James Alison, describes the stranger as the “Forgiving Victim.” It’s a provocative image. Think about it. Jesus is the first murder victim in history to be raised from the dead. He returns to forgive the lynch mob who murdered him, and this includes all those who abandoned him in his time of need, such as Cleopas and his friend.

Most of us are blind to the presence of such mercy. We literally can’t see it. In fact, many linguists believe we can only see that for which we have language. Where we lack language we lack sight, or as Stanley Hauerwas suggests,

“We can only act within the world we see, and we can only see what we can say.”

Sadly, many of us have never been given the language to know or even begin to imagine a God in whom there is no violence. Something like this is what’s happening on the road to Emmaus. Cleopas and his friend are being given the language and narrative that allows them to see the forgiving victim who walks with them – who reveals a God who is in rivalry with nothing, not even death. Humans, who are shot through with rivalry, have no categories for such a being. We are blind to such a being, until it reveals itself to us in terms we can understand.

For nearly 25 years the Street Psalms Community has been walking the road to Emmaus, learning to recognize the presence of the stranger among us. It takes a long time (usually a lifetime) to fully recognize this presence. We are only beginning to be given the language that helps us see the presence of mercy in our midst.

Like the disciples, we find ourselves changing course. We find ourselves returning to the scene of the crime – not in some masochistic act of penance, or some heroic act of dogooderism, but because we are experiencing the joyful freedom of having our story told by Jesus, the forgiving victim, who is in rivalry with nothing, not even death. Our eyes are being opened and our hearts burn within.

Join us. Let’s walk together.

Peace,

Kris Rocke

Executive Director

*Curiously, archeologists have never found Emmaus. It seems that Luke is using Emmaus as a metaphor. In other words, Luke is inviting us to see the road to Emmaus as a road to literally nowhere – a road most of us know quite well. And then there’s the fact that Cleopas’ friend in the story is unnamed. Perhaps this is Luke’s way of inviting us to insert ourselves into the text and imagine ourselves meeting the stranger on the road to Emmaus.