See. Do. Be. Free.

Issue 012

An Open Letter to the Community around this year's theme.

Greetings,

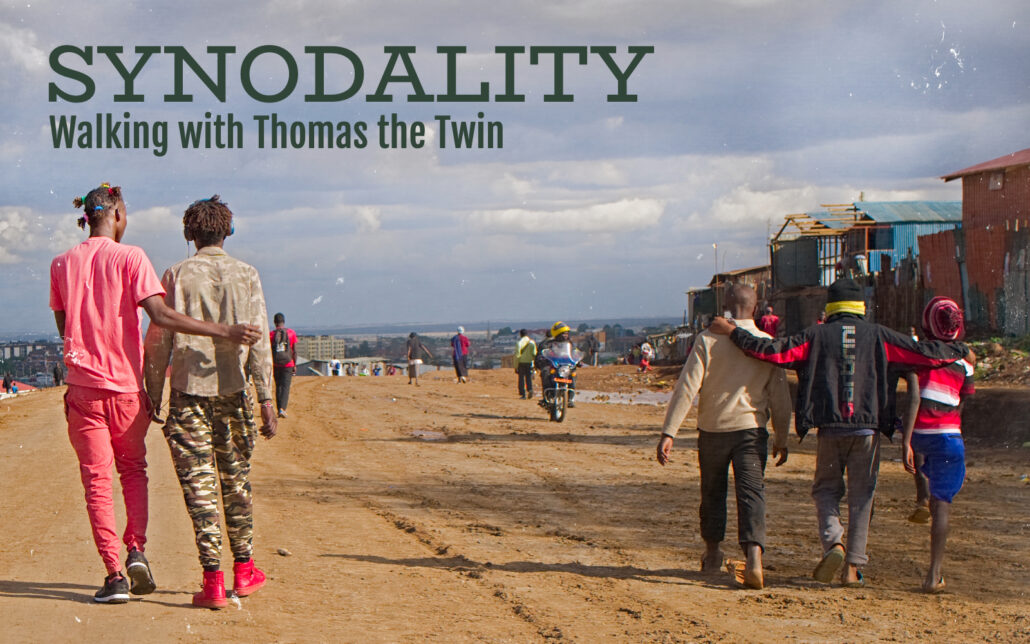

This year’s theme is synodality. It means “walking together” We are learning what it means to walk together across difference for the sake of the most vulnerable. In the end, we discover something we didn’t expect – our sameness.

This month we are walking with Thomas who bore the nickname Didymus. Didymus means “twin” in Greek. Thomas also means “twin” in Aramaic. So, Thomas Didymus means “Twin, Twin.”

Very strange!

Thomas’ signature moment in the Gospels is when he meets Jesus in the resurrection and insists on touching Jesus’ wounds (John 20:24-29). Unfortunately, the nickname that stuck is “Doubting Thomas” not “Thomas the Twin,” which is how the text refers to him.

What’s going on here?

Did Thomas have a twin sibling? Was there something in his character that earned him this nickname? The text does not explain the moniker, but Thomas is referred to as “the twin” several times in the Gospels, so the name clearly matters.

My wife is an identical twin. She and her sister not only look a lot alike but they once bought the same birthday card for each other, and secretly exchanged classes at school. They are both nurses who work at the same hospital. They are best friends who love each other dearly. They can also push each other’s buttons with lightning speed.

Throughout most of history twins were not seen as the blessing they are today. In fact, in the ancient world twins were seen as a threat to the social cohesion of society. They were the reminder that conflict ensues from sameness not difference. That is why they were often sacrificed (I’m not making this up). If this sounds strange, it’s only because we live in an age that is preoccupied with difference. This is especially true in Western culture where we worship at the altar of individuality. We cling to our perceived differences. We are deeply committed to the idea of the individual as an autonomous being with its own unique desires. Seeing ourselves mirrored in another person or group, can be intensely disorienting and a threat to our highly cultivated sense of self. Think about the people who easily get under our skin – it’s not the ones who are most different that really bother us. It’s the ones who are most like us, who want and compete for the same things as us.

The social sciences are discovering what the ancient world knew so well. We are learning that humans are immensely social creatures who are socially constructed at levels that render the concept of “individual” largely meaningless. We might want to think of ourselves as snowflakes (no two are alike) and that we have our own unique desires, but as anthropologist Rene Girard suggests, humans are not the individuals we think we are and communities are not the autonomous creations we imagine them to be. We don’t have intrinsic, autonomous desires. Instead, as Girard insists, “We borrow our desires from the desires of others.” Girard calls this process “mimesis.” In the same way that gravity is a hidden force that impacts every aspect of the natural world, mimetic desire is a hidden force that impacts every aspect of the social world. It’s how we decide what clothes to wear, the cars we drive, and even the spouses we choose. It’s a revolutionary insight.

And if Girard is right, then we are much more connected and alike than we imagined. Every attempt to distinguish ourselves as different only makes us more alike and draws us deeper into potential conflict. The thought that we are equally human with no greater or lesser claim on favor (from God or others) is joyfully liberating, but not before it’s intensely disorienting. This is the struggle that twins represent.

Consider perhaps the most famous twins in history – Jacob and Esau. They were rivals from the beginning as they wrestled within their mother’s womb for status and favor (Genesis 25:21-34). They wrestled throughout their lives, and their wrestling match continued even after their deaths. Their sibling rivalry became tribal rivalry. The shortest book in the Old Testament, called Obediah, is about the conflict between the descendants of Jacob and Esau. Is it any coincidence then that Jesus is from the line of Jacob and Herod is from the line of Esau?

Sibling rivalry! This might very well describe the human condition.

As I see it, we are confronted with two choices.

Either we imitate the love we see in Jesus, and cultivate a peaceful community that can accept our sibling sameness. Or, we imitate the fear we see in each other and end up in violent chaos fueled by the lie of difference.

If this sounds confusing, let me try to clarify.

When society is in chaos (as it is now) we become fascinated with, and fixated on, our “enemies.” Without knowing it, we end up borrowing our desires so thoroughly from those we dislike that we become twin doubles of our enemies. We become structurally the same as those we hate and everyone can see it except those of us who are caught in the rivalry. Think of the Hatfields and McCoys, Bloods and the Crips, Republicans and Democrats, Protestants and Catholics (the list goes on). Sworn enemies are absolutely committed to seeing each other as fundamentally different, but in all the ways that really matter, they are twin doubles of each other. Even worse, they are ruled by what they hate in the other, enslaved to it. In a huge ironic twist, when violence finally erupts, all differences between us are lost. We are never more alike than when we are at each other’s throats. This is the nature of violence.

Jesus comes to show us another way. Jesus shows us that when our attention is fixed on God, and we practice borrowing our desires from the One who is in rivalry with nothing, not even death, then we can begin to experience another kind of sameness – one that is no longer a threat. Let’s call it oneness. “Father, may they be one just as you and I are one” (John 17:21).

So what if Thomas, who is nicknamed “the twin”, is not so much the paragon of doubt, but the possibility of healing sibling rivalry? When Thomas puts his finger into the side of Jesus he is doing much more than simply overcoming his doubts by verifying the presence of the risen Christ. He is mirroring the life of Christ who comes to touch our wounds. He is encountering the reality of One who bears the wounds of the world with forgiveness. He is encountering the possibility that wounds really are wombs of new creation bearing seeds of new life when held in mercy. In touching the wounds of the risen Christ, Thomas is twinning these possibilities. By imitating Jesus, who is our sibling, he is accepting our shared humanity and showing us the path to healing.

Thomas is giving us a glimpse of this kind of community. He is borrowing his desires from the One who is in rivalry with nothing and it frees Thomas to do the same. In touching the wound of Jesus, He is imitating Jesus, becoming his twin. He went on to enflesh the spirit of Jesus he so thoroughly imitated. According to tradition, Thomas traveled the farthest of any of the disciples. He went to southern India where he showed up as a wounded healer and very much the twin double of Jesus.

This year we set out to learn what it means to be a synodal community who walks together across difference. The shockingly good news is that we are also discovering our sameness. We are learning to celebrate what we hold in common. We are all siblings. We are all human! This discovery happens when we dare to touch Jesus’ wounds and discover our own wounds held in love. How else will we create cities of peace for all people where everyone belongs?

Peace,

Kris Rocke